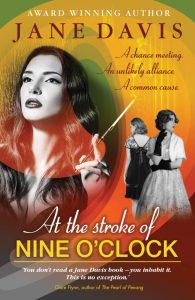

Today I’m delighted to welcome award-winning author Jane Davis back to the blog to talk about her latest book At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock.

Today I’m delighted to welcome award-winning author Jane Davis back to the blog to talk about her latest book At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock.

I always enjoy reading Jane’s novels and I’m especially looking forward to this one, her tenth, because it sounds so intriguing.

In this interview Jane talks about the inspiration behind At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock and what she might be doing next.

Congratulations on publishing your tenth novel. Please tell us about the inspiration behind At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock and what sort of story readers can look forward to.

Although fiction is my first love, I also read quite a few biographies. My own family history has taught me that you couldn’t get away with ‘making up’ some of the things that happen in real life. Readers would claim that there were too many coincidences.

Although fiction is my first love, I also read quite a few biographies. My own family history has taught me that you couldn’t get away with ‘making up’ some of the things that happen in real life. Readers would claim that there were too many coincidences.

What happened was this: I read three biographies about three very different women, all of whom lived through the 1950s. In each, the subject had a connection with Ruth Ellis, the last woman to be hanged in Great Britain.

I turned to my bookshelves for a yellowed paperback that has been in my possession for over thirty years. Ruth Ellis: A Case of Diminished Responsibility? I’d forgotten that the book begins with a foreword by co-authors Laurence Marks and Tony Van Den Bergh in which they reveal how, during their research, they both discovered that they had various links to players in the story of Ruth Ellis, if not Ellis herself: one of David Blakely’s other lovers; the partner of a psychiatrist who had treated Ruth Ellis; the brother of the manageress of the Steering Wheel club who had thrown Blakely and Ellis out for having a drunken fight on the premises just days before the shooting; the Catholic priest who, while serving as a prison chaplain sat on the Home Office committee tasked with deciding if Ellis was fit to hang. The list went on.

But even those who had never met Ellis had an opinion about her, and all were affected by her demise. Feelings ran so high that her case added significant weight to the arguments against capital punishment. Within two years of Ellis’s execution, The Homicide Act 1957 became law, limiting the death penalty by restricting it to certain types of murder, followed in 1965 by the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act.

All stories need an angle. Taking the demise of Ruth Ellis as your starting point, how did you choose to tell this story?

I think it would have been difficult to write about such recent history from Ruth Ellis’s perspective – added to which, what I wanted to write about was people’s reaction to her conviction and sentencing.

The 1950s was a decade when dual standards were still very much at play. Women were punished for daring to step outside the restricted confines that society had decided they should remain within. Sex outside marriage, divorce, and children born outside wedlock were huge taboos, but there is no doubt that things were happening.

I chose to use three very different women to tell the story, all of whom would have their own personal reason to say, ‘There, but for the grace of God’.

The first character to make an appearance is Caroline Wilby. She’s seventeen years old, and like many seventeen-year-olds of the day, she’s expected to contribute to her family’s income. Pressure is ramped up by the fact that her father has left them – although Caroline’s mother has insisted that she keep this fact secret. For Caroline, this means leaving the family home in Felixstowe and moving to London. She soon discovers options for a young woman with little education are limited and, where work is available, the wages barely cover her own keep, let alone leave her with money over to send home. We quickly see her putting herself at risk, accepting invitations from men she barely knows, and following much the same route that Ruth Ellis followed – firstly working as a photographer’s model and then as a hostess at a private members’ club. The dangers of being alone in a strange city are amplified by the frenzy the press has created around John Haigh, the so-called Acid Bath Murderer, who invented plausible stories to explain the disappearance of his victims.

Then we have Ursula Delancy, an actress who has scandalised the world of filmdom by leaving her husband and daughter for Hollywood film director, Donald Flood. This is the era when studios ‘owned’ their signings, dictating how they should look and behave, even how much they should weigh. Up until 1934, Hollywood had been relatively liberal, but along came William Hays, a government-hired Presbyterian pastor, who laid out a strict moral code dictating how Hollywood – and America – would behave for generations to come. Ursula is one of those who made it onto Hays’s Doom Book of blacklisted actors – those considered ‘unsuitable’. Still, she firmly believes that when she marries her Hollywood director, the public will see that theirs wasn’t some sordid little affair. Unfortunately, that isn’t to be. She has returned to England for a season in the West End (where, again, she is playing the part of a saintly figure) and is already under siege by the British press when she discovers that she has been usurped, and the ‘other woman’ is not just anyone but Donald’s ex-wife, Lindsay. And in an added twist, Lindsay is also pregnant with Donald’s child.

My trio is completed by a duchess. Patrice Hawtree has already suffered her fair share of scandal, but is rather more practised at managing the press than Ursula. She and her husband Charles came close to ruin when Charles lent his name to a conman named Davenport who set up a fake investment scheme and absconded with the investors’ money. To save their social standing, the Hawtrees compensated those who lost their life savings, including some of their closest friends. Doing so cost them dearly, but they expected a line to be drawn under the matter. Instead they’ve been ostracised. Aware that Charles’s judgement cannot be trusted, Patrice believes that she’s kept him on a very tight rein, but I’m afraid she’s about to be disillusioned. And the extent of his deception is something not even she will be willing to believe.

Does At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock share themes with your previous work? What do you think your main themes are?

Does At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock share themes with your previous work? What do you think your main themes are?

I’m afraid I’m gunning for the press again, just as I was in Smash all the Windows. In At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock, I describe how the press of the day created a frenzy around murder trials, speculating about what the murderers did immediately before and after they killed. Ruth Ellis was newspaper gold.

“Six revolver shots shattered the Easter Sunday calm of Hampstead and a beautiful platinum blonde stood with her back to the wall. In her hand was a revolver…” Bam!

The public was hooked by the story of the blonde hostess (who was also a divorcee), who shot her racing-boy lover in cold blood. You had this unreal situation where tickets for Ruth’s Old Bailey trial changed hands for upwards of thirty pounds.

The fact that this tragedy was treated as entertainment is horrific. Ruth was a young woman, a mother of two. She may have done little to defend herself, and that appears to have been her choice, but her admission of guilt means that nobody really tried to discover why she did it. And cause and effect is what always grips a writer.

Having published nine previous novels, can you describe your writing process? Do you find it gets easier over time?

I like George R R Martin’s quote: ‘I’ve always said there are two kinds of writers. There are architects and gardeners. Architects do blueprints before they drive the first nail, they design the entire house, where the pipes are running and how many rooms there are going to be, how high the roof will be. But the gardeners just dig a hole and plant the seed and see what comes up.’ Personally, I think there are more than two types of writers. I want to be Mary Anning scouring the beaches at Lyme Regis for dinosaur fossils, or Howard Carter discovering the tomb of Tutankhamun, or metal detectorist Terry Herbert digging up the Staffordshire Hoard. What I don’t want to be is a parent deciding on my child’s future, telling my son which subjects he will study, arranging my daughter’s marriage.

Once I have self-edited the manuscript to the stage where I can’t be objective, I send it out to beta readers. The importance of this stage in the process is clear. The aim is to road-test the story by giving it to people with a wide range of life experiences. It’s said that the reader finishes the book, so I’m keen to know how they react to it before finally letting it off its leash. Then come more changes, the copy edit and several rounds of proof-reading.

I’m afraid that anyone who imagines that words show up in the eventual order that they appear on the page of any novel is (in the majority of cases) mistaken. In some ways, the novel in its final form is an illusion, the rabbit pulled out of the hat.

As for whether it gets any easier, if anything, I think the reverse is true. Once you’ve established a loyal readership, whatever size that readership may be, you don’t want to let them down!

Do you find it difficult to let go of a book, or are you already thinking about the next one?

I do find it hard to move on, but I’ve been working away at this project for over two and a half years, so once publication is out of the way, I think I’ll be ready to move on. The question is ‘What to?’

I have an idea for a novel, but the other project that I’ve had on the go is the diary I kept about caring for my father who had dementia. (He passed away in April.) I’m not quite sure what to do with it yet, except that I’d like it to be meaningful.

One in fifteen adults over the age of 65 suffers from some form of dementia. By the time you reach the age of 80, the odds increase to one in six (and for many of these people, dementia will be one of several health conditions they suffer from). And yet talking about dementia seems to be taboo.

I have so many incredible anecdotes that might provide reassurance to those whose relatives have a diagnosis. Another approach would be to produce a serious work of non-fiction, perhaps about how little help is available for the army of unpaid carers who are looking after family members. My mother was my father’s full-time carer (and believe me, caring for Dad was a 24-four-hour-a-day job). In October 2018 Mum was hospitalised with a serious infection that came about because she’d neglected her own healthcare needs. On leaving hospital, she should have been entitled to a carer herself. Instead, she was straight back into the role of caring for my father. I wish I could say that her experience was isolated, but from what we hear, this is all too common.

Here’s a short extract:

14th October 2018, 12.30am. I am staying at the house because Mum has just come out of hospital. Dad is up and dressed, cutting out newspaper clippings. He looks very tired.

Jane: Hello, Dad. I could have sworn I put you to bed two hours ago.

Dad: Where did you come from?

Jane: I was asleep in the back bedroom.

Dad: Yes, but who are you?

Jane: I’m Jane. Your daughter.

Dad: Jane? (Incredulous)

Jane: Come on, let me show you. (I take Dad to the hall and point to my photograph.)

Dad: That’s you?

Jane: That’s me, 26 years ago.

Dad: Are you sure? (Looks closely at me.) But your hair is all funny. (Tries to flatten it down.)

Jane: I expect I need to brush it.

Dad: (Happy now) Shall we have a nice cup of coffee and some of the little round things? (He means biscuits.)

Jane: I think we should both go to bed. It’s the middle of the night.

Dad: I know. It’s ridiculous!

Jane: It’s very dark outside.

Dad: Because of the rain. (For the last two days, I have been telling Dad it is dark in the daytime because it has been raining. Now I regret it.)

Jane: How about it? Shall we go upstairs to bed?

Dad: Shhhh. If you have some blankets, you can still be very cosy. Come on, let me show you. (Shows me his reclining armchair in the sitting room and pats the seat.) You sleep here.

Jane: How about you sit down, Dad, and I’ll do the blankets for you?

Dad: But when is the coffee?

Jane: You sit down and I’ll tuck you in and make you a nice coffee.

Dad: Oh, (nonchalant), I suppose so.

Dad is fast asleep by the time I bring his coffee.

2.30 a.m. Dad is ‘restoring’ one of his father’s self-portraits with Blu-tack.

Jane: Hello, Dad, I see you’re up again.

Dad: We have to put it in the holes, and we press it in and then we leave it for a few days.

Jane: Perhaps we could do that in the morning. It’s the middle the night.

Dad: (Holds my head in both hands and gives me a Latin blessing). You worry too much.

Jane: I expect I do.

Dad: Where is the person who makes the porridge?

Jane: Mum? I hope she’s fast asleep.

Mum: (Standing on staircase.) No, she isn’t!

Now we are all up in the kitchen and it is the middle of the night. I decide one of us should really go to bed so that Dad doesn’t think it is time to get up. Mum insists it is me.

Next day, Dad is up bright and breezy at 6.00am. Meanwhile Mum and I are exhausted.

###

Thanks for the interview, Jane, and good luck with your upcoming release!

London 1949. The lives of three very different women are about to collide.

Like most working-class daughters, Caroline Wilby is expected to help support her family. Alone in a strange city, she must grab any opportunity that comes her way. Even if that means putting herself in danger.

Star of the silver screen, Ursula Delancy, has just been abandoned by the man she left her husband for. Already hounded by the press, it won’t be long before she’s making headlines for all the wrong reasons.

Patrice Hawtree was once the most photographed debutante of her generation. Now childless and trapped in a loveless marriage, her plans to secure the future of her ancient family home are about to be jeopardised by her husband’s gambling addiction.

Each believes she has already lost in life, not knowing how far she still has to fall.

Six years later, one cause will unite them: when a young woman commits a crime of passion and is condemned to hang, remaining silent isn’t an option.

“Why do I feel an affinity with Ruth Ellis? I know how certain facts can be presented in such a way that there is no way to defend yourself. Not without hurting those you love.”

Hailed by The Bookseller as ‘One to Watch’, Jane Davis is the author of nine thought-provoking novels.

Jane spent her twenties and the first part of her thirties chasing promotions at work, but when she achieved what she’d set out to do, she discovered that it wasn’t what she wanted after all. It was then that she turned to writing.

Her debut, Half-truths & White Lies, won the Daily Mail First Novel Award 2008. Of her subsequent three novels, Compulsion Reads wrote, ‘Davis is a phenomenal writer, whose ability to create well-rounded characters that are easy to relate to feels effortless’. Her 2015 novel, An Unknown Woman, was Writing Magazine’s Self-published Book of the Year 2016 and has been shortlisted for two further awards. Smash all the Windows was the inaugural winner of the Selfies (best independently-published work of fiction) award 2019.

Jane lives in Carshalton, Surrey with her Formula 1 obsessed, star-gazing, beer-brewing partner, surrounded by growing piles of paperbacks, CDs and general chaos. When she isn’t writing, you may spot her disappearing up a mountain with a camera in hand. Her favourite description of fiction is ‘made-up truth’.