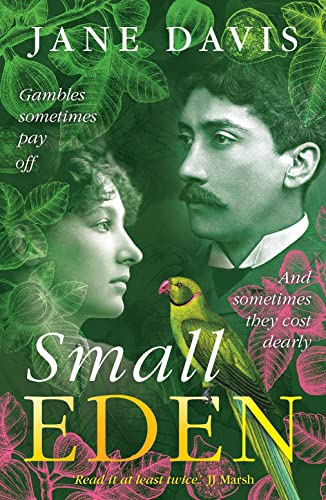

A new novel by Jane Davis is always welcome. Set in the 19th century, her tenth novel, Small Eden, is a beautifully evoked story about grief, loss, and the redemptive power of creation.

A boy with his head in the clouds. A man with a head full of dreams.

1884. The symptoms of scarlet fever are easily mistaken for teething, as Robert Cooke and his pregnant wife Freya discover at the cost of their two infant sons. Freya immediately isolates for the safety of their unborn child. Cut off from each other, there is no opportunity for husband and wife to teach each other the language of their loss. By the time they meet again, the subject is taboo. But unspoken grief is a dangerous enemy. It bides its time.

1884. The symptoms of scarlet fever are easily mistaken for teething, as Robert Cooke and his pregnant wife Freya discover at the cost of their two infant sons. Freya immediately isolates for the safety of their unborn child. Cut off from each other, there is no opportunity for husband and wife to teach each other the language of their loss. By the time they meet again, the subject is taboo. But unspoken grief is a dangerous enemy. It bides its time.

A decade later and now a successful businessman, Robert decides to create a pleasure garden in memory of his sons, in the very same place he found refuge as a boy – a disused chalk quarry in Surrey’s Carshalton. But instead of sharing his vision with his wife, he widens the gulf between them by keeping her in the dark. It is another woman who translates his dreams. An obscure yet talented artist called Florence Hoddy, who lives alone with her unmarried brother, painting only what she sees from her window…

In this article, Jane shares with us some of her research for the book.

Setting Free the Parakeets

Adding to the urban myths about the origins of London’s green ring-necked parakeets

No respectable Eden would be complete without birds. Several species feature in my tenth novel, Small Eden. First, we have the songbirds in the hedgerows and the pleasure gardens. There’s Hettie’s grey African parrot Fairfax (a personality in his own right). And then we have the green ring-necked parakeets Robert Cooke buys for the aviary in his pleasure garden.

No respectable Eden would be complete without birds. Several species feature in my tenth novel, Small Eden. First, we have the songbirds in the hedgerows and the pleasure gardens. There’s Hettie’s grey African parrot Fairfax (a personality in his own right). And then we have the green ring-necked parakeets Robert Cooke buys for the aviary in his pleasure garden.

I live close to Beddington Park, once a hunting ground of royals and nobles and now home to one of the UK’s largest flocks of green ring-necked parakeets. One of the reasons for their tremendous success is because their breeding season starts before Britain’s native species return from wintering grounds, allowing them to secure the best nesting sites. But the parakeets’ success isn’t all bad news. They provide smaller birds with protection against predation. Crows, starlings and jackdaws are all intimidated by parakeets. And, according to the Natural History Museum, they are London peregrines’ second favourite meal (pigeons still top that unenviable list).

Originally imported for sale as exotic pets, green ring-necked parakeets are Britain’s only naturalised parrot. Speculation about how these tropical birds came to populate London and Surrey in such great numbers has given rise to several urban myths.

The African Queen Connection

According to some, London’s green ring-necked parakeets arrived in 1951 when Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn were filming The African Queen at Shepperton Studios. Apparently, a number of parakeets recruited as extras for the film escaped from the set. Certainly, parakeets in their dozens can be seen feasting at garden feeders by the side of the Thames. There are, however, a couple of snags. Although The African Queen was a London-based production, it was actually filmed at Worton Hall Studios in Isleworth (with a surprising number of scenes being shot on location in Africa). Also, no parakeets. Not a single one.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience

Others say that Jimi Hendrix strolled down Carnaby Street in 1968 with a birdcage in hand, and released two bright green birds he had named Adam and Eve as a symbol of peace. (By the sixties, birds were more popular pets than cats and dogs in the UK, with 11 million being kept in captivity.)

The Syon Park Connection

It has been suggested that birds escaped from an aviary at Syon Park in the 1970s when it was damaged by debris falling from an aircraft, or, even more dramatically, when a plane crashed through the aviary, depending on your source. You’d think that it would be possible to find records about a plane crashing through the roof of an aviary at Syon Park. Good luck with that.

The George Michael Connection

More recently, stories have emerged that a pair escaped during a row between George Michael and Boy George who shared a flat in Brockley in the 1980s. Or that burglars broke into George Michael’s Hampstead home in the 1990s and raided his aviary. Whichever it was, it definitely had something to do with George Michael.

A classic case of research ruining a perfectly good story

As much as we’d like these theories to be true, the application of geographic profiling – a technique originally developed in criminology, but now applied to ecology and conservation biology – has disproved them. The technique involves mapping the locations referred to in the theories and applying the model to biological data – in this case, DNA taken from the UK’s parakeet population. This revealed no links. Instead, studies have concluded the reason they are so populous is likely to be a consequence of repeated releases and introductions.

Living on familiar terms with sparrows

Victorians kept parakeets as pets and there were sightings of wild parakeets as early as the 1800s. According to the Essex Herald, in 1886 a breeding pair with five offspring were living ‘on familiar terms’ with sparrows in the trees of Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Parrot disease scares

In 1932, the Middlesex County Times reported that parakeets had been spotted in Epping Forest and Loughton Cemetery. The newspaper credited the ‘parrot disease scare’ of 1931 for an increase in the deliberate release of pet birds into the wild. (Psittacosis is a respiratory disease that can jump from birds to people and can result in pneumonia.) In 1932 the Ministry of Health banned the import of parakeets after The Londonderry Sentinel published an article about the death of a parakeet-owner. The ban remained in force for two decades. With headlines urging the public to keep away from dangerous birds, people no longer wanted them in their homes, and wouldn’t it have been more humane to release them rather than kill them? In the early 1950s parrot flu hit the headlines again after a Birmingham man died, and domestic poultry and ducks were found to be infected. A ban was again placed on imports.

The Great Storm

After a trickle of sightings, the UK’s parakeet population grew rapidly between 1986 and 1999. According to The Journal of Zoology, the most plausible origin story is that their numbers shot up after birds escaped from various aviaries that suffered damage during the Great Storm of 1987 (the very same storm that I wrote about in These Fragile Things).

Here to stay

Today, green ring-necked parakeets are firmly established as far north as Glasgow’s Victoria Park (said to be the most northerly flock of parrots in the world.) It looks as if they’re here to stay. It amused me to add to their story.

How can I pre-order Small Eden?

Just use the universal link and click on your preferred store. The eBook will be delivered to you on 30 April, which in the UK is the beginning of our spring bank holiday.

Where can we follow you on social media?

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/janedavisauthor

- Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/JaneDavisAuthorPage

- Blog/web url: https://jane-davis.co.uk

Author biography

Jane Davis’ first novel, ‘Half-Truths and White Lies’, won a national award established with the aim of finding the next Joanne Harris. Further recognition followed in 2016 with ‘An Unknown Woman’ being named Self-Published Book of the Year by Writing Magazine/the David St John Thomas Charitable Trust, as well as being shortlisted in the IAN Awards, and in 2019 with ‘Smash all the Windows’ winning the inaugural Selfies Book Award. Her novel, ‘At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock’ was featured by The Lady Magazine as one of their favourite books set in the 1950s, selected as a Historical Novel Society Editor’s Choice, and shortlisted for the Selfies Book Awards 2021.

Jane Davis’ first novel, ‘Half-Truths and White Lies’, won a national award established with the aim of finding the next Joanne Harris. Further recognition followed in 2016 with ‘An Unknown Woman’ being named Self-Published Book of the Year by Writing Magazine/the David St John Thomas Charitable Trust, as well as being shortlisted in the IAN Awards, and in 2019 with ‘Smash all the Windows’ winning the inaugural Selfies Book Award. Her novel, ‘At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock’ was featured by The Lady Magazine as one of their favourite books set in the 1950s, selected as a Historical Novel Society Editor’s Choice, and shortlisted for the Selfies Book Awards 2021.

Interested in how people behave under pressure, Jane introduces her characters when they are in highly volatile situations and then, in her words, she throws them to the lions. The themes she explores are diverse, ranging from pioneering female photographers, to relatives seeking justice for the victims of a fictional disaster.

Jane Davis lives in Carshalton, Surrey, in what was originally the ticket office for a Victorian pleasure gardens, known locally as ‘the gingerbread house’. Her house frequently features in her fiction. In fact, she burnt it to the ground in the opening chapter of ‘An Unknown Woman’. In her latest release, ‘Small Eden’, she asks the question why one man would choose to open a pleasure gardens at a time when so many others were facing bankruptcy?

When she isn’t writing, you may spot Jane disappearing up the side of a mountain with a camera in hand.